Suffering and letting go

Khổ Đau Và Buông Xả

English: Ajahn Brahm

Việt ngữ: Chơn Quán Trần-ngọc Lợi

Compile: Lotus group

43. Khổ Đau Và Buông Xả - Suffering and letting go – Song ngữ

Chương 11: Khổ Đau Và Buông Xả - Suffering and letting go

96. Thinking about washing - Nghĩ về chuyện giặt y

Washing robes in the traditional way of the forest monks

People these days think too much. If they would only quieten their thinking process a little, then their lives would flow much easier.

Con người trong thời đại ngày nay có quá nhiều suy tư. Nếu họ bớt suy nghĩ một chút, chắc họ sẽ sống thoải mái hơn.

One night each week in our monastery in Thailand, the monks would forgo their sleep to meditate all night in the main hall. It was part of our forest monk’s tradition. It wasn’t too austere since we could always take a nap the following morning.

Trong tự viện chúng tôi ở Thái, mỗi tuần chúng tôi bỏ ngủ một đêm để thiền từ chạng vạng tới rạng đông tại chánh điện. Thật tình không có gì gọi là khắc khổ lắm vì chúng tôi có thể ngủ bù vào sáng hôm sau.

One morning after the all-night meditation session, when we were about to go back to our huts to catch up on our sleep, the abbot beckoned a junior Australian-born monk. To the monk’s dismay, the abbot gave him a huge pile of robes to wash, ordering him to do it immediately. It was our tradition to look after the abbot by washing his robes and doing other little services for him.

Lần nọ, sau đêm thiền lúc chúng tôi chuẩn bị về cốc nghỉ ngơi, sư cả bảo vị tỳ kheo người Úc đem một ôm y đi giặt ngay, khiến ai ai cũng đều ngạc nhiên. Tập tục của chúng tôi là phải luôn luôn chăm lo cho sư cả trụ trì, như giặt y hay rửa bình bát của sư.

This was an enormous pile of washing. Moreover, all washing had to be done in the traditional way of the forest monks. Water had to be hauled from a well, a big fire made and the water boiled. A log from a jack fruit tree would be pared into chips with the monastery’s machete. The chips would be added to the boiling water to release their sap, which would act as the ‘detergent’. Then each robe would be placed singly in a long wooden trough, the brown boiling water poured over, and the robe would be pounded by hand until it was clean. The monk had then to dry the robes in the sun, turning them from time to time to ensure that the natural dye did not streak. To wash even one robe was a long and burdensome process. To wash such a large number of robes would take many hours. The young Brisbane-born monk was tired from not sleeping all night. I felt sorry for him.

Đống y khá lớn và phải giặt tay. Theo truyền thống dạy, phải xách nước giếng, chẻ gỗ mít lấy dăm nấu với nước (làm xà bông), đặt y từng chiếc một trên cái máng, đổ nước sôi (màu nước nâu nâu vì mủ mít) lên y, và dùng tay vò y. Y sạch phải được phơi ngoài nắng và phải được trở đúng lúc để màu không phai y không bị lem luốc. Giặt một chiếc y theo cách truyền thống này đã là một việc rất công phu và đòi hỏi nhiều thời gian rồi, vậy mà sư gốc Brisbane (Thủ phủ của Queensland, một trong ba thành phố lớn nhất của Úc, nằm trên bờ biển Đông của châu Úc) kia phải giặt tới một đống y sau đêm thiền không ngủ. Thật đáng thương sư!

I went over to the washing shed to give him a hand. When I got there, he was swearing and cursing more in Brisbane tradition than Buddhist tradition. He was complaining how unfair and cruel it was. ‘Couldn’t that abbot have waited until tomorrow? Didn’t he realize that I haven’t slept all night? I didn’t become a monk for this!’ That was not precisely what he said, but this is all that is printable.

Tôi ra chòi giặt để phụ sư một tay. Tôi ngạc nhiên biết sư làm công phu theo truyền thống Brisbane hơn là truyền thống Phật giáo. Sư cằn nhằn sao sư cả không đợi qua hôm sau rồi hãy sai đi giặt? Sư cả có biết sư không ngủ suốt đêm qua không? Sư đi tu chớ đâu phải đi ở đợ! Đây không phải là nguyên văn sư nói nhưng ý sư là như vậy.

When this occurred, I had been a monk for several years. I understood what he was experiencing and knew the way out of his problem. I told him, ‘Thinking about it is much harder than doing it.’

Qua những năm trải nghiệm cuộc đời là sư, tôi biết tâm trạng của sư đang giặt y này. Tôi bèn khuyên sư: “Nghĩ đến công việc mệt hơn là làm công việc ấy.”

He fell silent and stared at me. After a few moments of silence, he quietly went back to work and I went off for a sleep. Later that day, he came to see me to say thank you for helping with the washing. It was so true, he discovered, that thinking about it was the hardest part. When he stopped complaining and just did the washing, there was no problem at all.

Sư nhìn tôi, lặng thinh. Rồi sư trở lại giặt y và sau đó đi ngủ. Chiều, sư đến gặp tôi cám ơn tôi đã giúp sư giặt xong đống y một cách gọn hơ. Sư thú nhận rằng nghĩ là phần khó nhất. Lúc sư không còn nghĩ và cằn nhằn nữa, việc giặt y của sư trôi qua dễ dàng.

The hardest part of anything in life is thinking about it.

Phần khó nhất của bất cứ việc gì trong cuộc sống là suy nghĩ quá nhiều về công việc ấy.

97. A moving experience - Kinh nghiệm xe đất

0

0

Forest monk’s shoveled and wheelbarrowed experience

I learned the priceless lesson that ‘the hardest part of anything in life is thinking about it’ in my early years as a monk in northeast Thailand.

Tôi học được bài học “nghĩ khổ hơn làm” lúc tôi theo tu học với Ajahn Chah ở Thái Lan.

Ajahn Chah was constructing his monastery’s new ceremonial hall and many of us monks were helping with the work. Ajahn Chah used to test us out by saying that a monk would work hard all day for just one or two Pepsis, which was much cheaper for the monastery than hiring laborers from town. Often, I thought of starting a trade union for junior monks.

Lúc bấy giờ Ajahn Chah đang xây cất chánh điện và tất cả các sư đều góp sức. Ajahn Chah thường thử chúng tôi bằng cách nói rằng công lao của một sư trong một ngày bằng hai chai nước ngọt Pepsi (đó là loại nước ngọt có khí hòa tan do hàng PepsiCo sản xuất. Thứ nước ngọt này được dược sĩ Caleb Bredlam ở New Bern, North Carolina Mỹ, chế tạo năm 1898 và trở thành thương hiệu năm 1903), rất rẻ so với lương trả cho công nhân mướn ở ngoài. Biết vậy, tôi nghĩ phải chỉ tôi lập một công đoàn sư trẻ!

The ceremonial hall was constructed on a monk-made hill. There was much earth remaining from the mound. So Ajahn Chah called us monks together and told us that he wanted the remaining earth moved around to the back. For the next three days, working from 10.00 a.m. until well past dark, we shoveled and wheelbarrowed that great amount of earth to the very place that Ajahn Chah wanted. I was happy to see it finished.

Chánh điện được cất trên đồi do các sư khai phá. Cất xong, đất còn dư khá nhiều. Ajahn Chah bảo chúng tôi xe đất đi đổ. Chúng tôi hì hục trong ba ngày liền, xúc đất xe đi đổ chỗ được chỉ định. Công việc rất vất vả, nhưng xong rồi, ai nấy đều hoan hỷ.

The following day, Ajahn Chah left to visit another monastery for a few days. After he left, the deputy abbot called us monks together and told us that the earth was in the wrong place and had to be moved. I was annoyed, yet I managed to subdue my complaining mind as we all labored hard for another three days in the tropical heat.

Hôm sau lúc Ajahn Chah đi vắng, sư phó trụ trì gọi chúng tôi bảo phải dời đất đi chỗ khác. Tôi nhớ lại ba ngày làm việc không kịp thở dưới ánh nắng cháy da vừa qua mà ngán ngẩm rồi đâm ra bực dọc. Nhưng rất may, tôi tự chế được và bắt tay vô làm.

Just after we had finished moving the heap of earth for the second time, Ajahn Chah returned. He called us monks together and said, ‘Why did you move the earth there? I told you it was to go in that other spot. Move it back there!’

I was angry. I was livid. I was ropeable. ‘Can’t those senior monks decide among themselves first? Buddhism is supposed to be an organized religion, but this monastery is so disorganized it can’t even organize where to put some dirt! They can’t do this to me!’

Three more long, tiring days loomed ahead of me. I was cursing in English, so the Thai monks wouldn’t understand me, as I pushed the leaden wheelbarrows. This was beyond the pale. When would this stop?

Ba ngày cực khổ nữa đang chực chờ chúng tôi. Lúc còng lưng đẩy xe đất, tôi rất bất mãn; tôi rủa bằng tiếng Anh nên các sư Thái không hiểu. Tôi nghĩ chỉ thị của sư trưởng lão không hợp lý và thử hỏi cái không hợp lý này còn kéo dài tới bao lâu nữa!

I began to notice that the angrier I was, the heavier the wheelbarrow felt. One of my fellow monks saw me grumbling, came over and told me, ‘Your trouble is that you think too much!’

Tôi có cảm tưởng tôi càng giận, xe đất càng nặng thêm. Thấy tôi vừa hì hục vừa lầm bầm, một sư bạn ngừng tay đến nói nhỏ với tôi rằng: “Vấn đề của sư là sư suy nghĩ nhiều quá!”

He was so right. As soon as I stopped whingeingly and whining, the wheelbarrow felt much lighter to push. I learned my lesson. Thinking about moving the earth was the hardest part; moving it was easy.

Nghe lời sư bạn, tôi không suy nghĩ và không than vãn nữa, tôi có cảm tưởng xe đất nhẹ ra và dễ đẩy hơn. Nghĩ đến việc xe đất khó hơn đẩy xe đất. Sư bạn tôi nói đúng và tôi học được chữ Nhẫn.

To this day, I suspect that Ajahn Chah and his deputy abbot planned it as it happened from the very start.

Giờ đây tôi nghĩ chắc hai sư trưởng lão của chúng tôi đã sắp đặt vậy ngay từ lúc đầu.

98. Poor me; lucky them - Buồn ta, vui họ!

Poor me; lucky them – Vui người, buồn ta!

Life as a very junior monk in Thailand seemed so unfair. The senior monks received the best food, sat on the softest cushions and never had to push wheelbarrows. Whereas my one meal of the day was disgusting; I had to sit for long hours in ceremonies on the hard-concrete floor (which was lumpy as well, because the villagers were hopeless at laying concrete); and sometimes I had to labor very hard. Poor me; lucky them.

Đời sống của sư trẻ ở Thái Lan xem chừng như không có gì có thể là công bằng hết. Sư lớn được ăn ngon, ngồi trên tọa cụ mềm và không phải đẩy xe bồ ệch (Âm của tiếng pháp Brouette, tức xe cút kít để chuyển đất, cây, cành, gạch, ngói v.v…). còn sư trẻ như tôi ăn những thứ chán phèo, dầu biết rằng bữa ăn ấy duy nhất trong ngày. Tôi ngồi hàng giờ dự lễ dưới sàn xi măng không phẳng phiu (vì dân quê làm gì biết cách tráng xi măng). Nhiều lúc tôi còn phải làm việc vất vả nữa. Buồn cho tôi, vui cho họ!

I spent long, unpleasant hours justifying my complaints to myself. The senior monks were probably so enlightened that delicious food would be wasted on them, therefore I should get the best food. The senior monks had been sitting cross-legged on hard floors for years and were used to it, therefore I should get the big soft cushions. Moreover, the senior monks were all fat anyway, from eating the best food, so had ‘natural upholstery’ to their posteriors. The senior monks just told us junior monks to do the work, never laboring themselves, so how could they appreciate how hot and tiring pushing wheel-barrows was? The projects were all their ideas anyway, so they should do the work! Poor me; lucky them.

Tôi bỏ nhiều thì giờ lý luận nhưng rồi cũng không đến đâu, chỉ đến sự than thân trách phận. Sư lớn đã ít nhiều giác ngộ rồi thì đâu còn bận tâm tới món ngon vật lạ; sư trẻ chúng tôi mới cần ăn ngon. Sư lớn đã quen ngồi trên sàn cứng rồi, họ nên nhường gối mền cho chúng tôi. Hơn thế nữa sư lớn nào cũng mập lù, họ có “gối mỡ thiên nhiên” rồi. Sư lớn cứ bảo chúng tôi cố gắng làm việc cho họ chẳng động tới móng tay. Vậy làm sao họ biết cái nóng của nắng hay cái mệt của sự đẩy xe nặng? Vả lại mọi chương trình đều do họ hoạch định, họ phải ra tay chớ! Buồn cho tôi, vui cho họ!

When I became a senior monk, I ate the best food, sat on a soft cushion and did little physical work. However, I caught myself envying the junior monks. They didn’t have to give all the public talks, listen to people’s problems all day and spend hours on administration. They had no responsibilities and so much time for themselves. I heard myself saying, ‘Poor me; lucky them!’

Lúc tôi lên hàng sư lớn, tôi ăn ngon, ngồi trên gối mềm và ít khi làm lụng vất vả. Nhưng tôi lại thích đời sống sư trẻ. Tôi nghe tôi tự nói với mình rằng: “Tôi khỏi phải thuyết pháp cho đại chúng, phải giải quyết vấn đề của người khác, khỏi phải lo việc hành chánh nhức đầu.” Buồn cho tôi, vui cho họ!

I soon figured out what was going on. Junior monks have ‘junior monk suffering’. Senior monks have ‘senior monk suffering’. When I became a senior monk, I was just exchanging one form of suffering for another form of suffering.

Tôi nhận thức rằng sư trẻ có cái khổ của sư trẻ, sư lớn có cái khổ của sư lớn. Từ sư trẻ lên sư lớn tôi chỉ đổi từ cái khổ này qua cái khổ khác.

It is precisely the same for single people who envy those who are married, and for married people who envy those who are single. As we all should know by now, when we get married, we are only exchanging ‘single person’s suffering’ for ‘married person’s suffering’. Then when we get divorced, we are only exchanging ‘married person’s suffering’ for ‘single person’s suffering’. Poor me; lucky them.

Cũng vậy, người độc thân mong được như người có gia đình và người có gia đình muốn được làm người độc thân. Giờ đây các bạn chắc đã hiểu rằng khi lập gia đình các bạn chỉ đổi “cái khổ của người độc thân” qua “cái khổ của người có gia đình”. Rồi khi bạn nào ly dị, bạn ấy chỉ đổi từ “cái khổ của người có gia đình” qua “cái khổ của người ly dị”.

When we are poor, we envy those who are rich. However, many who are rich envy the sincere friendships and freedom from responsibilities of those who are poor. Becoming rich is only exchanging ‘poor person’s suffering’ for ‘rich person’s suffering’. Retiring and taking a cut in your income is only exchanging ‘rich person’s suffering’ for ‘poor person’s suffering’. And so, it goes on. Poor me; lucky them.

Lúc nghèo chúng ta mong được giàu. Nhưng có nhiều người giàu muốn trở lại thời nghèo, lúc họ vui cái vui chân thật giữa bạn bè hay hưởng thú tự do muốn đi đâu thì đi (không sợ ai bắt cóc đòi chuộc mạng hoặc cà rà theo xin tiền). Họ chuyển từ “cái khổ của người nghèo” qua “cái khổ của người giàu”. Người về hưu bị bắt giảm lợi tức, họ chuyển từ “cái khổ của người giàu” qua “cái khổ của người nghèo” và câu chuyện “Buồn tôi, vui họ!” kéo dài bất tận.

To think that you will be happy by becoming something else is delusion. Becoming something else just exchanges one form of suffering for another form of suffering. But when you are content with who you are now, junior or senior, married or single, rich or poor, then you are free of suffering. Lucky me; poor them.

Nghĩ rằng mình sẽ hạnh phúc khi được cái này hay cái khác là ảo tưởng. “Trở thành” là một hình thức chuyển đổi từ cái khổ này qua cái khổ khác mà thôi. Chỉ khi nào chúng ta mãn nguyện với cái mình hiện có, chúng ta mới thật sự hạnh phúc. Và chừng đó mới “Vui ta, buồn họ!”

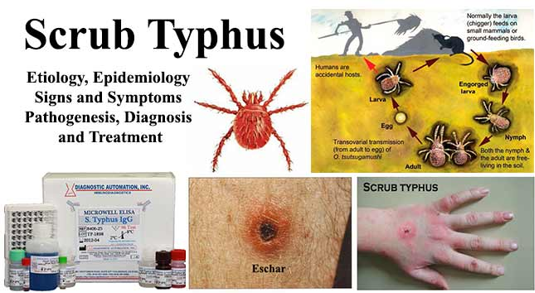

99. Advice for when you are sick - Lời khuyên người bệnh

Scrub Typhus - Bệnh sốt phát ban do chấy, rận từ chuột cắn…

In my second year as a monk in northeast Thailand, I came down with scrub typhus. The fever was so strong that I was admitted to the monks’ ward in the regional hospital at Ubon. In those days, in the mid-1970s, Ubon was a remote backwater of a very poor country.

Tôi bị “Bệnh sốt phát ban” lúc đang tu tại Thái Lan, tu năm thứ hai. Tôi bị hành nóng lạnh, phải nhập viện ở Ubon và được đưa vô nằm trong khu dành riêng cho tu sĩ. Vào giữa thập niên 70 Ubon còn là một vùng quê xa xôi hẻo lánh rất nghèo nàn.

Feeling weak and afflicted, with a drip in my arm, I noticed the male nurse leave his station at 6.00 p.m. Half an hour later, the replacement nurse had yet to arrive, so I asked the monk in the next bed if we should alert someone in charge that the night nurse hadn’t come. I was quickly told that in the monks’ ward, there never is a night nurse. If you take a turn for the worse during the night, that’s just unlucky karma. It was bad enough being very sick; now I was terrified as well!

Đến nơi tôi cảm thấy mệt nhoài, tay nhân bủn rủn và yếu hẳn người. nhưng phòng không có y tá trực; y tá trực ngày rời viện lúc 6:00 chiều rồi. Chừng nửa giờ sau không thấy có y tá khác thay thế, tôi hỏi sư nằm bên cạnh và được biết khu này không có y tá trực ban đêm. Sư ấy còn nói thêm rằng nếu có gì xảy ra cho sư nào thì đó là vì cái nghiệp của sư ấy vậy! Bệnh đã lo rồi, nghe sư này nói tôi cảm thấy sợ thêm!

For the next four weeks, every morning and afternoon a nurse built like a water buffalo would inject my buttocks with antibiotics. This was a poor public hospital in an undeveloped area of a third-world country, so the needles were recycled many more times than would be allowed even in Bangkok. That strong-armed nurse literally had to stab the needle with considerable force to enter the flesh. Monks were expected to be tough, but my buttocks weren’t: they became very sore. I hated that nurse at that time.

Đúng là nghiệp của mình nó hành; tôi phải chịu trận nằm lại đây một tháng trường. Mỗi sáng và chiều tôi bị anh y tá, mạnh như trâu, lụi kim vô mông - chích cho thuốc kháng sinh. Là một cơ sở y tế nghèo trong vùng lạc hậu của một quốc gia thuộc thế giới thứ ba, bệnh viện tôi nằm phải dùng đi dùng lại kim và ống chích luộc trong nước sôi. Kim cũ rất lụt nên anh y tá phải ráng sức đâm mạnh làm tôi ê ẩm cả hai mông. Tôi sợ và ghét anh y tá trâu cổ này không thể tả!

I was in pain, I was weak, and I had never felt so miserable in my life. Then, one afternoon, Ajahn Chah came into the monks’ ward to visit me. To visit me! I felt so flattered and impressed. I was uplifted. I felt great—until Ajahn Chah opened his mouth. What he said, I later found out, he told many sick monks whom he visited in hospital. He told me, ‘You’ll either get better, or you’ll die.’

Tôi đau đớn, tôi yếu người và tôi khổ sở vô cùng. Một chiều nọ Ajahn Chah đến, Ngài đến thăm tôi? Đúng, Ngài thăm tôi và các sư khác đang nằm tại đây. Tôi rất cảm kích và hãnh diện. Tôi rất vinh hạnh và cảm thấy vui nhiều - cho đến khi Ngài lên tiếng: “Sư phải ráng hết bệnh nếu không sư sẽ chết.”

(Ajahn Chah lặp lại câu nói này với mọi bệnh nhân Ngài đến thăm chiều hôm ấy, tôi biết được như vậy hồi sau này).

Then he went away.

My elation was shattered. My joy at the visit vanished. The worst thing was that you couldn’t fault Ajahn Chah. What he said was absolute truth. I’ll get better or I’ll die. Either way, the discomfort of the sickness will not last. Surprisingly, that was very reassuring. As it happened, I got better instead of dying. What a great teacher Ajahn Chah was.

Lúc ngài ra về, tôi thất vọng ê chề; niềm vui được Ngài đến thăm viếng tan tành theo mây khói. Và cái đau buồn nhất của tôi là tôi không được nghi ngờ lời của một bậc trưởng lão như Ajahn Chah, vì điều gì Ngài nói ra đều là sự thật hết. Tôi phải ráng hết bệnh, nếu không tôi sẽ chết. Hai ngã đường sanh tử, ngã nào cũng xóa tan mọi đau khổ của bệnh tật cả.

Đó là sự thật. Và may cho tôi, tôi được đi qua “ngã sanh” nhờ bệnh thuyên giảm và hết luôn.

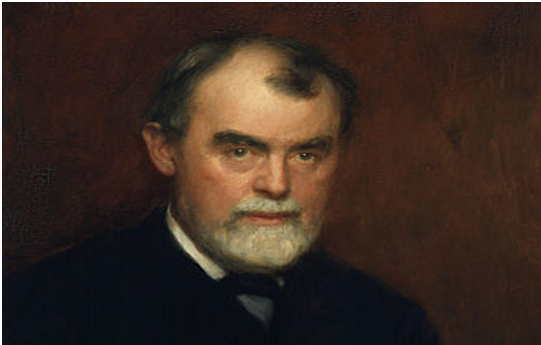

100. What’s wrong with being sick? - Ngã bệnh là một cái tội?

Samuel Butler (1835 – 1902) - novel Erewhon 1872 - …tưởng tượng bệnh tật được xem như cái tội đáng bị tù…

In my public talks, I often ask the audience to raise their hand if they have ever been sick. Nearly everyone puts up their hand. (Those who don’t are either asleep or probably lost in a sexual fantasy!) This proves, I argue, that it is quite normal to be sick. In fact, it would be very unusual if you didn’t fall sick from time to time. So why, I ask, do you say when you visit the doctor, ‘There is something wrong with me, doctor’? It would be wrong only if you weren’t sick sometimes. Thus, a rational person should say instead, ‘There is something right with me, doctor. I’m sick again!’

Trong nhiều buổi nói chuyện tôi thường yêu cầu thính chúng giơ tay nếu họ đã từng bị bệnh. Hầu hết đưa tay lên (những người không giơ tay có thể đang ngủ gục hay đang mơ mộng chuyện gì đó). Đó cho thấy bệnh là chuyện bình thường. Hơn thế nữa, bạn sẽ bất bình thường nếu thỉnh thoảng bạn không bị bệnh. Như vậy tại sao khi gặp bác sĩ bạn lại khai sức khỏe tôi bình thường? Bạn không khi nào bị bệnh mới là chuyện bất thường, có phải không nào?

Whenever you perceive sickness as something wrong, you add unnecessary stress, even guilt, on top of the unpleasantness. In the nineteenth-century novel Erehwon, Samuel Butler envisaged a society in which illness was considered a crime and the sick were punished with a jail term. In one memorable passage, the accused man, sniffling and sneezing in the dock, was berated by the judge as a serial offender. This was not the first time he had appeared before the magistrate with a cold. Moreover, it was all his fault through eating junk food, failing to exercise adequately, and following a stressful lifestyle. He was sentenced to several years in jail.

Lúc nào bạn nghĩ rằng đau ốm là “cái bất thường” bạn đã vô tình gây thêm phiền não vô ích cho bạn. Trong tiểu thuyết Erewhon (Erewhon là tiểu thuyết giả tưởng châm biếm thời nữ hoàng Alexandrina Victoria (1819 – 1910) trị vì Anh quốc) xuất bản năm 1872, tác giả Samuel Butler tưởng tượng một xã hội trong ấy bệnh tật được xem như cái tội đáng bị tù. Một bị cáo đang đứng trước vành móng ngựa bất chợt ho và nhảy mũi (ông đang bị bệnh à!) bị ông chánh án kết tội là người tái phạm nhiều lần. Đó không phải là lần đầu tiên ông ra tòa. Hơn thế nữa, đó là hậu quả của việc ăn uống bừa bãi trong môi trường đầy căng thẳng. Ông bị kết án nhiều năm tù giam!

How many of us are led to feel guilty when we are sick?

Có ai trong chúng ta cảm thấy bị tội khi đau ốm?

A fellow monk had been sick with an unknown illness for many years. He would spend day after day, week after week, in bed all day, too weak even to walk beyond his room. The monastery spared no expense or effort arranging every kind of medical therapy, orthodox and alternative, in an attempt to help him, but nothing seemed to work. He would think he was feeling better, stagger outside for a little walk, and then relapse for weeks. Many times, they thought he would die.

Một vị sư bạn của tôi mang chứng bệnh không biết căn nguyên trong nhiều năm. Ông nằm gần như liệt giường tháng này qua tháng kia, không con sức đi đứng dầu chỉ đi ra khỏi cốc. Tự viện không tiếc tiền cũng như công sức để giúp sư điều trị bằng tây y cả đông y, nhưng không có hiệu quả. Nếu có, chỉ là hiệu quả tạm thời rồi đâu cũng vào đó. Ai cũng đinh ninh sư sẽ chết.

One day, the wise abbot of the monastery had an insight into the problem. So, he went to the sick monk’s room. The bedridden monk stared up at the abbot with utter hopelessness.

Lần nọ vị sư trụ trì quán chiếu vấn đề và tìm được một phương pháp. Ngài đến cốc thăm sư bệnh nhân và nói:

‘I’ve come here,’ said the abbot, ‘on behalf of all the monks and nuns of this monastery, and also for all the laypeople who support us. On behalf of all these people who love and care for you, I have come to give you permission to die. You don’t have to get better.’

“Tôi đến đây, thay mặt cho toàn thể các tăng ni trong tự viện cũng như tất cả Phật tử hộ trì từng quý mến Sư, cho phép sư được chết. Sư không cần bình phục nữa.”

At those words, the sick monk wept. He’d been trying so hard to get better. His friends had gone to so much trouble trying to help heal his sick body that he couldn’t bear to disappoint them. He felt such a failure, so guilty, for not getting better. On hearing the abbot’s words, he now felt free to be sick, even to die. He didn’t need to struggle so hard to please his friends anymore. The release he felt caused him to cry.

Sau khi nghe lời sư cả, sư bệnh khóc. Lâu nay ông đã cố gắng hết sức mình để mong hồi phục. Hơn thế nữa ông không thể phản bội các sư bạn đã từng đổ công sức giúp ông lành bệnh. Ông cảm thấy mình thất bại và tội lỗi nếu không ngồi dậy nổi. Lời của sư cả cho biết giờ đây ông tự do bệnh và chết cũng được. Ông không cần phải cố gắng để làm vui lòng thầy bạn nữa. Sự giải thoát làm ông chảy nước mắt.

What do you think happened next? From that day on, he began to recover.

Bạn nghĩ vị sư bệnh này có chết không? Không. Từ hôm ấy, sư thấy bệnh mình thuyên giảm và sau rốt sư hết bệnh.

101. Visiting the sick - Thăm bệnh

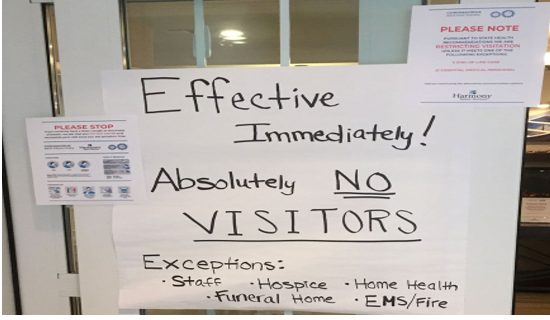

Không tiếp khách ngoại trừ nhân viên bệnh viện…

How many of us say, ‘How are you feeling today?’ when visiting a loved one in hospital?

“Anh có khỏe không?” là câu trên đầu môi của người đi vô nhà thương thăm bệnh. Có phải vậy không các bạn?

For a start, what a stupid thing to say! Of course, they’re feeling rotten, otherwise they wouldn’t be in hospital, would they? Furthermore, the common greeting puts the patient in profound psychological stress. They feel it would be an act of rudeness to upset their visitors by telling the truth that they feel terrible. How can they disappoint someone who has taken the time and trouble to come and visit them in hospital by honestly replying that they feel awful, as drained as a used tea bag? So instead, they may feel compelled to lie, saying, ‘I think I feel a little better today’, meanwhile feeling guilty that they aren’t doing enough to get better. Unfortunately, too many hospital visitors make the patients feel more ill!

Thật ngô nghê! Nếu khỏe thì anh ấy vô bệnh viện làm gì? Hơn thế nữa câu hỏi đó chỉ làm tinh thần người bệnh thêm căng thẳng. Anh sẽ cảm thấy mình không tế nhị nếu trả lời thật tình rằng mình đau chỗ này hay chỗ nọ. Anh cũng sẽ cảm thấy mình vô tâm nếu hé lộ sự thật có thể làm cho người đã bỏ công đến bệnh viện thăm mình đau buồn. Do đó, anh phải nói láo, “À tôi khá hơn hôm qua” để rồi sẽ ân hận là mình đã mang tội chưa khá mà nói khá và tội nói láo. Tiếc chưa? Người thăm bệnh đã vô tình làm bệnh nhân bệnh thêm!

An Australian nun of the Tibetan Buddhist tradition was dying of cancer in a hospice in Perth. I had known her for several years and would visit her often. One day she phoned meat my monastery, requesting I visit her that very day as she felt her time was close. So, I dropped what I was doing and immediately got someone to drive me the seventy kilometers to the hospice in Perth. When I checked in at the hospice reception, an authoritarian nurse told me that the Tibetan Buddhist nun had given strict instructions that no one was to visit her.

Một ni người Úc thuộc dòng Tây tạng bị ung thư, đang chờ chết tại nhà chờ ở Perth. Tôi biết ni cô nhiều năm qua và thường đến thăm viếng bà. Một hôm bà gọi yêu cầu tôi đến thăm bà ngay trong nội nhật vì bà có cảm tưởng sẽ đi bất cứ giờ phút nào. Thế là tôi bỏ hết công việc nhờ xe chở đi bảy mươi cây số để gặp bà lần sau cùng. Đến nơi tôi được lễ tân cho biết ni cô đã dặn không cho ai thăm cả.

‘But I have come from so far specially to see her,’ I gently said.

‘I’m sorry,’ barked the nurse, ‘she does not want any visitors and we all must respect that.’

‘But that cannot be so,’ I protested. ‘She phoned me only an hour and a half ago and asked me to come.’

“Nhưng tôi đã đi bảy mươi cây số ngàn để chỉ thăm ni cô,” tôi nài nỉ.

“Rất tiếc” cô y tá nói “bà không muốn khách thăm và chúng tôi phải tôn trọng ý muốn của bà”

“Nhưng bà ấy gọi tôi cách đây một tiếng rưỡi yêu cầu tôi đến” tôi chống chế.

The senior nurse glared at me and ordered me to follow her. We stopped in front of the Aussie nun’s room where the nurse pointed to the big paper sign taped to the closed door.

‘ABSOLUTELY NO VISITORS!’

‘See!’ said the nurse.

As I examined the notice, I read some more words, written in smaller letters underneath: ‘... except Ajahn Brahm.’

So, I went in.

Cô y tá trưởng tò mò nhìn tôi rồi ra dấu mời tôi theo cô. Chúng tôi dừng lại trước cửa phòng của ni cô. Cô chỉ lên bảng dán trên tường, “Không tiếp khách” và nói, “Đó sư thấy không?”

Tôi đọc kỹ bảng viết và thấy thêm hàng chữ nhỏ “trừ Ajahn Brahm” bên dưới. Thế là tôi được vào.

When I asked the nun why she had put up the notice with the special exception, she explained that when all her other friends and relations came to visit her, they became so sad and miserable seeing her dying that it made her feel much worse. ‘It’s bad enough dying from cancer’, she said, ‘but it’s too much to deal with my visitors’ emotional problems as well.’

Tôi hỏi sao ni cô cho viết bảng như vậy, bà đáp rằng tất cả khách thăm đều tỏ ra buồn rầu khi thấy bà sắp chết nên bà không chịu nổi.

“Chết vì ung thư đã khổ rồi, phải đối phó với tình cảm của khách thăm bệnh còn khổ hơn,” Ni cô giải thích.

She went on to say that I was the only friend who treated her as a person, not as someone dying; who didn’t get upset at seeing her gaunt and wasted, but instead told her jokes and made her laugh. So, I told her jokes for the next hour, while she taught me how to help a friend with their death. I learnt from her that when you visit someone in hospital, talk to the person and leave the doctors and nurses to talk to the sickness.

She died less than two days after my visit.

Rồi bà nói tiếp rằng tôi là người duy nhất xem bà như người bình thường, chớ không phải người bệnh đáng thương. Tôi còn nói chuyện đùa để làm bà vui và chọc bà cười. Được mời, tôi kể chuyện cười suốt một tiếng đồng hồ. Đáp lại, bà dạy tôi cách giúp bệnh nhân sắp chết. Bài học tôi học là khi vào nhà thương ta nên nói chuyện thường với người thường và hãy để bác sĩ nói chuyện bệnh với bệnh nhân.

Ni cô qua đời hai ngày sau khi tôi đi thăm bà lần ấy.

102. The lighter side of death - Làm vơi nỗi u sầu của tang chế

Traditional Buddhist Vietnamese Funeral (chaobuoisang.net)

As a Buddhist monk, I often have to deal with death. It is part of my job to conduct Buddhist funeral services. As a result, I know many of the funeral directors in Perth on a personal basis. Perhaps it is because of the requirement for public solemnity that in private they show a great sense of humor.

Làm sư tôi có nhiệm vụ cử hành tang lễ và thường trực diện với cái chết. Do đó tôi quen - quen khá thân với nhiều giám đốc nhà quàn. Họ luôn luôn nghiêm trang trong tang lễ nhưng rất hài hước trong đời tư.

For instance, one funeral director told me of a cemetery in South Australia located in a clay-based hollow. They had seen it happen several times, they told me, that just after they had lowered the coffin into the grave, a heavy shower would come and water would pour into the hole. With the priest saying the prayers, the coffin would slowly float up into full view!

Ví dụ có một giám đốc từng kể cho tôi nghe chuyện của cái nghĩa địa trong vùng đất sét trũng sâu ở miền Nam Úc. Hễ có hạ huyệt là có mưa lớn. Và trong lúc cha xứ làm lễ, quan tài từ từ nổi lên!

Then there was the vicar in Perth who, at the very beginning of the service, inadvertently leant on all of the buttons on the lectern. All at once, and in the middle of his reading, the coffin began moving through the curtain, his microphone cutout, and the bugle calls of The Last Post reverberated through the chapel! It didn’t help that the deceased was a pacifist.

Một chuyện khác: trong lúc đọc kinh, cha sở ở Perth vô ý dựa vào hàng nút trên bục giảng khiến âm thanh bị tắt, nhạc kèn đám ma thổi bản Last Post (Last Post là bản nhạc dùng trong các tang lễ quân lực để tiễn người chiến sĩ ra đi vĩnh viễn. Sử dụng lần đầu tiên trong quân lực hoàng gia Anh. Thường thổi bằng kèn đồng bugle.) vang vang và quan tài lù lù chạy ra qua màn chắn. Chuyện xảy ra làm nhiều người dự đám tang nghĩ quấy rằng thân xác trong quan tài kia không thể nào là một người ôn hòa trong lúc sanh tiền!

One particular funeral director was of the habit of telling me jokes as we walked together ahead of the hearse, and the following cortege, through the cemetery to the grave side. At the punch line to each of his jokes, which were all very funny, he would dig me in the ribs with his elbow and try to make me laugh. It was all I could do to resist laughing out loud. So, as we approached the place for the service, I had to tell him very firmly to stop misbehaving so I could arrange my face in a countenance more befitting to the occasion. That only incited him to begin another joke, the swine!

Một giám đốc khác có tật nói giễu lúc cùng tôi đi trước xe tang trên đường từ nhà quàn tới nghĩa địa. Sau mỗi chuyện – mà chuyện nào cũng đáng cười hết – ông thúc cùi chỏ cho tôi cười. Tôi không sao không cười nhưng không dám cười ra tiếng. Biết vậy, tôi luôn luôn nhắc ông đừng giễu lúc tôi làm lễ; tôi cần bộ mặt nghiêm nghị. Yêu cầu của tôi chỉ làm ông giễu thêm.

Over the years, though, I have learned to lighten up at my Buddhist funerals. A few years ago, I summoned up the courage to tell a joke for the first time at a funeral service. Shortly after I began the joke, the funeral director, standing at the back of the bereaved, figured out what I was about to do and made faces at me, desperately trying to make me stop. It is simply not done to crack a joke at a funeral service. But I was determined. The funeral director’s face went whiter than one of his corpses. At the end of the joke, the mourners in the chapel broke freely into laughter, and the funeral director’s once-contorted face relaxed with relief. The family and friends all congratulated me afterwards. They said how much the deceased would have enjoyed that particular joke and how he would have been pleased that his loved ones had sent him off with a smile. I often tell that joke at funeral services now. Why not? Would you like your relations and friends to hear me tell a joke at your funeral service? Every time I have asked that question, the answer is always ‘Yes!’

Lâu rồi tôi học và biết phải làm gì để đám tang bớt u buồn. Lần nọ cách nay khá lâu, tôi bậm gan kể câu chuyện vui trong đám tang tôi chủ lễ. Sau khi tôi bắt đầu câu chuyện, ông giám đốc tang lễ đứng sau đám người đưa tang ra dấu cho tôi ngưng vì ông nghĩ không nên làm như vậy trong nhà quàn. Nhưng tôi cứ tiếp tục khiến mặt ông còn nhăn hơn mặt thân chủ của ông đang bật cười. Họ nói người quá cố chắc sẽ vui nhiều khi thấy thân thuộc đưa ông đi bằng nụ cười nở trên môi. Từ đó tôi bắt đầu kể chuyện vui trong đám tang nhằm mục đích làm vơi đi phần nào nỗi u sầu của thân quyến và các bạn bè đi đưa.

Tại sao không phải không các bạn? Và bạn có muốn tôi kể chuyện cười trong đám tang của bạn không? Mỗi lần tôi hỏi như vậy, thính chúng đều đồng thanh đáp, “Muốn!”

So, what was that joke?

Vậy thì có gì mà phải lo! Và dưới đây là một chuyện:

An elderly couple had been together so long that when one passed away, the other died only a few days later. Thus, they appeared in heaven together. A beautiful angel took them both to an impressive mansion on top of a cliff overlooking the ocean. In this life, only billionaires could afford such outstanding real estate. The angel announced that the mansion was theirs as their heavenly reward.

Có hai ông bà nọ sống chung nhau rất lâu, cho đến già khụ. Lúc ông chết bà chết theo chỉ vài hôm sau đó. Cả hai đều lên thiên đường, họ được một tiên nữ duyên dáng đưa đến một biệt thự to trên ngọn đồi có sóng vỗ quanh năm, thứ biệt thự mà đại phú gia mới tạo nổi trên thế gian này. Tiên nữ trình rằng biệt thự này là phần thưởng tiên giới của hai ông bà.

The husband had been a practical man and immediately said, ‘That’s all very well, but I don’t think we could afford the annual council rates on such a big property.’ The angel smiled sweetly and told them that there were no government taxes on property in heaven. Then he took the couple on a tour of the many rooms in the mansion. Each room was furnished in exquisite taste, some with antique furniture, some with modern. Priceless chandeliers dripped from many ceilings. Taps of solid gold gleamed in every bathroom. There were DVD systems and state-of-the-art widescreen televisions. At the end of the tour, the angel said that if there was anything they didn’t like, just let him know and he would change it at once. This was their heavenly reward.

The husband had been reckoning the value of all the contents and said, ‘These are very expensive furnishings. I don’t think we could afford the property insurance premium.’

The angel rolled his eyes and told them gently that thieves weren’t allowed to enter heaven, so there wasn’t any need for property insurance.

Là người thực tế, ông vội nói: “Rất tuyệt nhưng chúng tôi làm sao đóng thuế nổi?” Tiên nữ mỉm cười, thưa rằng trên thiên đường không có thuế nhà đất. Nói xong, tiên nữ đưa ông bà đi một vòng xem biệt thự. Tất cả các phòng đều được trang hoàng bàn ghế, tủ giường hoặc cổ hoặc tân, rất đắt tiền. Đèn trần cái nào cái nấy đều lộng lẫy. Bồn rửa mặt, bàn cầu bằng vàng đặc. Truyền hình đầu máy thứ tối tân nhất thế giới. Sau khi xem qua hết rồi, tiên nữ trịnh trọng trình đó là quà tiên giới của ông bà. Nếu có món nào ông bà không vừa ý, xin báo cho biết là có người đến thay ngay.

Ông không che giấu sự e ngại và nói thẳng với tiên nữ rằng ông bà không đủ tiền đóng bảo hiểm cho các thứ quý hiếm như vậy. Cô tiên nữ đáp ngay rằng trên thiên đường không có trộm cắp nên không cần phải bảo kê.

Then he led them both downstairs to the mansion’s triple-spaced garage. There was a huge, new SUV four-wheel drive next to a glittering Rolls- Royce Touring limousine, and the third car was a limited-edition red Ferrari sports car with retractable roof. The husband had always wanted a powerful sports car in his earthly life, but could only dream of ever owning one. The angel said that if they wished to change the models, or the colors, they should not hesitate to let him know. This was their heavenly reward.

Tiếp theo tiên nữ đưa ông bà ra nhà xe. Ba chiếc xe hiệu đang đậu chờ ông bà trong nhà xe ba gian rộng rãi này. Chiếc SUV (Viết tắt của chữ Sport Utility Venicle) đồ sộ, hai cầu, chạy luồn bốn bánh. Chiếc Touring Limousine Rolls – Royce sang trọng. Và không thấy lúc còn dưới thế. Tiên nữ xin ông bà cứ tự tiện thay đổi kiểu hay màu, chỉ cần báo là có liền. Đó là quà tiên cảnh của ông bà.

The husband glumly said, ‘Even if we could afford the vehicle registration fees, which we can’t, what’s the point of a fast sports car these days? I’ll only end up getting fined for speeding.’

Ông lo lắng nói: “Dẫu chúng tôi có thể đóng thuế số xe, điều mà chúng tôi không thể, chúng tôi cũng không dám nhận xe, vì xe thể thao để làm gì, nếu không muốn nói là để bị phạt vì chạy quá tốc độ!”

The angel shook his head and told them patiently that there were no vehicle registration fees up in heaven, nor were there any speed cameras. He could drive the Ferrari as fast as he liked. Then the angel opened the garage doors. On the opposite side of the road was a magnificent eighteen-hole golf course. The angel said that they knew up in heaven how much the husband liked his golf, adding that this wonderful golf course had been designed by Tiger Woods himself.

Tiên nữ lắc đầu thưa rằng trên thiên đường không có thuế bảng số cũng như không có công an rình bấm tốc độ. Ông có thể lái Ferrari chạy mau chậm gì tùy ý. Rồi cô bấm nút mở cửa nhà xe. Bên kia đường là sân gôn mười tám lỗ. Tiên nữ thưa tuy ở trên thiên đường nhưng ai cũng biết ông thích chơi gôn nên đã nhờ Tiger Woods (Tiger Woods (1975 - ) là nhà vô địch thế giới về gôn hiện nay, từng đoạt nhiều giải quốc tế lớn hàng năm từ 1997. Cha ông là người Mỹ da đen và mẹ ông là người Thái) cố vấn thiết kế sân gôn tuyệt vời này.

Still the husband looked unhappy as he said, ‘That is an expensive looking golf club, judging by the clubhouse, and I don’t think I could afford the club fees.’

“Sân gôn này ắt phải thâu hội phí rất đắt” ông nói, “tôi không nghĩ tôi có thể đóng nổi!”

The angel groaned, then recovering his saintly composure reassured the husband that there are no fees in heaven. Moreover, in golf courses in heaven you never have to queue to tee off, the ball always misses the bunkers, and the greens are so designed that whichever way you putt the ball, it will always curl into the hole. This was their heavenly reward.

Tiên nữ thưa: “Không có hội phí, nguyệt liễm trên thiên đường.” Cô nói thêm: “Vả lại trên sân này ông không phải cắm cơ mới đánh banh được. Banh biết tránh chướng ngại và luôn luôn về lỗ một cách chính xác. Đó là món quà tiên cảnh của ông bà.”

After the angel left them, the husband began to scold his wife. He was so angry with her that he yelled and ranted and reprimanded her something terrible. She couldn’t understand why he was so angry.

Sau khi tiên nữ xin cáo lui và ra về, ông la bà, la mắng một cách dữ dội. Ngạc nhiên, bà hỏi:

‘Why are you so upset at me?’ she pleaded, ‘We have this wonderful mansion and lovely furniture. You’ve got your Ferrari, which you may drive as fast as you want, and a golf course just across the road. Why are you so angry at me?’

“Tại sao ông la rầy tôi? Chúng ta được một biệt thự sang trọng nguy nga, bàn ghế lộng lẫy, xe Ferrari mà ông từng mơ ước, và sân gôn tuyệt vời kế bên nhà. Ông còn muốn gì nữa chớ? Và tại sao ông giận tôi quá đáng như vậy?

‘Because, wife,’ the husband said bitterly, ‘if it wasn’t for all that health food you gave me, I could have been up here years ago!’

“Tại bà hết,” ông chua chát nói, “tại dưới đó bà dọn cho tôi toàn món dinh dưỡng. Nếu không tôi đã lên đây từ lâu rồi!”

103. Grief, loss and celebrating a life - Sầu Muộn, Mất Mát và Mừng cho cuộc sống

Grief is what we add on to loss. It is a learned response, specific to some cultures only. It is not unavoidable.

Hễ có mất mát là có sầu muộn. Chúng đi chung với nhau như hình với bóng trong một số văn hóa, nhưng không hẳn là một hệ quả không có ngoại lệ.

I found this out through my own experience of being immersed for over eight years in a pure, Asian-Buddhist culture. In those early years in a Buddhist forest monastery in a remote corner of Thailand, Western culture and ideas were totally unknown. My monastery served as the local cremation ground for many surrounding villages. There was a cremation almost weekly. In the hundreds of funerals, I witnessed there in the late 1970s, never once did I see anyone cry. I would speak with the bereaved family in the following days and still there were no signs of grief. One had to conclude that there was no grief. I came to know that in northeast Thailand in those days, a region steeped in Buddhist teachings for many centuries, death was accepted by all in a way that defied Western theories of grief and loss.

Tôi có nhận xét trên sau tám năm tu học Phật tại miền Đông Bắc Thái Lan, nơi mà văn hóa và tư tưởng Tây Phương hầy như không được biết đến. Tự viện của tôi được dân làng sống chung quanh đó dùng làm nơi hỏa táng người quá cố, nên tôi có dịp chứng kiến hằng trăm đám tang trong cuối thập niên 70; mỗi tuần đều có ít nhất một đám. Tôi lấy làm lạ không thấy ai khóc trong đám tang. Thăm viếng và hỏi han, tôi được biết dân quê Thái tại vùng này không tỏ ra u buồn khi thân nhân họ ra đi; họ chấp nhận cái chết như chuyện thường tình vì đã thấm nhuần lời Phật dạy về sanh lão, bệnh, tử. Quan niệm của họ về cái chết và u sầu có nhiều khác biệt với quan niệm của phương Tây.

Those years taught me that there is an alternative to grief. Not that grief is wrong, only that there is another possibility. Loss of a loved one can be viewed in a second way, a way that avoids the long days of aching grief.

My own father died when I was only sixteen. He was, for me, a great man. He was the one who helped me find the meaning of love with his words, ‘Whatever you do in your life, Son, the door of my heart will always be open to you.’ Even though my love for him was huge, I never cried at his funeral service. Nor have I cried for him since. I have never felt like crying over his premature death. It took me many years to understand my emotions surrounding his death. I found that understanding through the following story, which I share with you here.

Ba tôi mất lúc tôi mới 16 tuổi. Đối với tôi ông là người cha tuyệt diệu. Chính ông đã dạy tôi, “Dầu con có làm gì trong đời con, tâm ba vẫn luôn luôn rộng mở.” Tôi quý ông vô cùng và thương ông yểu mệnh, nhưng tôi không khóc khi ông nhắm mắt lìa trần hay trong đám tang của ông và cả cho tới hôm nay. Tôi biết lý do tôi không khóc, và tôi xin kể câu chuyện sau để các bạn hiểu tại sao.

As a young man I enjoyed music, all types of music from rock to classical, jazz to folk. London was a fabulous city in which to grow up in the 1960s and early 1970s, especially when you loved music. I remember being at the very first nervous performance of the band Led Zeppelin at a small club in Soho. On another occasion, only a handful of us watched the then unknown Rod Stewart front a rock group in the upstairs room of a small pub in North London.

Lúc còn trong lứa tuổi thanh niên, tôi rất thích nhạc, từ nhạc rock đến cổ điển và jazz đến dân ca. Luân Đôn là thành phố mà ai đã yêu nhạc phải yêu Luân Đôn, nhất là trong hai thập niên 60 và 70. Tôi là một trong những người đầu tiên đi xem nhóm Led Xeppelin (nhóm nhạc rock thành lập năm 1968 bởi bốn nhạc sĩ Anh: John Bonham, Robert Plant, Jimmy Page, và John Paul Jones. Được gọi là “Ban nhạc lớn nhất thế giới” (1971 – 7) trình tấu tại hội quán nghèo Soho của thời bấy giờ. Tôi cũng tiên phong trong việc ủng hộ nhom rock của Rod Stewart (Roderick David “Rod” Stewart (1945-) nhà sáng tác nhạc rock và ca sĩ nổi tiếng của Anh Quốc từ 1960 đến nay) tại phòng tối tăm trên lầu của một quán rượu nhỏ ở phía Bắc thành phố.

I have so many precious memories of the music scene in London at that time.

At the end of most concerts I would shout ‘More! More!’ along with many others. Usually, the band or orchestra would play on for a while. Eventually, though, they had to stop, pack up their gear and go home. And so did I. It seems to my memory that every evening when I walked home from the club, pub or concert hall, it was always raining. There is a special word to describe the dreary type of rain often met with in London: drizzle. It always seemed to be drizzling, cold and gloomy as I left the concert halls. But even though I knew in my heart that I probably would never get to hear that band again, that they had left my life forever, never once did I feel sad or cry. As I walked out into the cold, damp darkness of the London night, the stirring music still echoed in my mind, ‘What magnificent music! What a powerful performance! How lucky I was to have been there at the time!’ I never felt grief at the end of a great concert.

Tôi còn giữ rất nhiều kỷ niệm của âm nhạc Luân Đôn thời bấy giờ. Sau mỗi lần trình diễn tôi thường cùng chúng bạn bụm tay hét lớn, “Thêm, thêm nữa!” Họ chơi thêm chút nữa, nhưng rồi sau cùng họ cũng cuốn gói. Và tôi cũng ra theo. Tôi còn nhớ mỗi lần tôi đi nghe nhạc về là gặp mưa, thứ mưa phùn dai dẳng lạnh lẽo và ảm đạm. Nhưng tôi không tiếc rẻ dầu cảnh có buồn và dòng nhạc đã dứt.

That is exactly how I felt after my own father’s death. It was as if a great concert had finally come to an end. It was such a wonderful performance. I was, as it were, shouting loudly ‘More! More!’ when it came close to the finale. My dear old dad did struggle hard to keep living a little longer for us. But the moment eventually came when he had to ‘pack up his gear and go home’. When I walked out of the crematorium at Mortlake at the end of the service into the cold London drizzle—I remember the drizzle clearly—knowing in my heart that I would probably not get to be with him again, that he had left my life forever, I didn’t feel sad; nor did I cry. What I felt in my heart was, ‘What a magnificent father! What a powerful inspiration was his life. How lucky I was to have been there at the time. How fortunate I was to have been his son.’ As I held my mother’s hand on the long walk into the future, I felt the very same exhilaration as I had often felt at the end of one of the great concerts in my life. I wouldn’t have missed that for the world. Thank you, Dad.

Đó là tâm trạng tôi lúc Ba tôi ra đi. Cũng như buổi hòa nhạc hay tới hồi chấm dứt. Thế thôi! Nếu tôi có van cầu, có thể ông sẽ nuối lại một khoảnh khắc nữa rồi sau cùng ông cũng “cuốn gói” ra đi. Lúc tôi từ lò hỏa táng Mortlake trở về, tôi cũng đi trong mưa phùn, tôi cũng biết rằng Ba tôi – một người cha tuyệt vời – không còn nữa! Nhưng tôi không khóc vì tôi nhận chân được sự thật và tôi đã may mắn được sống với ông, được ông dạy dỗ, được làm con ông, ít ra là cũng có một thời gian mười sáu năm. Cám ơn, Ba!

Grief is seeing only what has been taken away from you. The celebration of a life is recognizing all that we were blessed with, and feeling so very grateful.

U sầu chỉ đến khi nào chúng ta cảm thấy mình bị mất mát. Còn vinh danh cuộc sống là nhận biết chúng ta may mắn có được và thầm cám ơn cái mà chúng ta có được đó.

104. Falling leaves - Lá Rụng

… many leaves that now lay spread thickly on the forest floor.

Probably the hardest of deaths for us to accept is that of a child. On many occasions I have had the honor to conduct the funeral service for a small boy or girl, someone not long set out on their experience of life. My task is to help lead the distraught parents, and others as well, beyond the torment of guilt and through the obsessive demand for an answer to the question, ‘Why?’

I often relate the following parable, which was told to me in Thailand many years ago.

Có lẽ cái chết mà chúng ta khó chấp nhận nhất là cái chết của trẻ con. Tôi có nhiều dịp cử hành tang lễ cho các em, trai cũng như gái, chưa biết mùi đời. Một trong những nhiệm vụ khác của tôi là khuyên giải thân nhân của các em để họ vơi phần nào u sầu và mặc cảm tội lỗi. Câu hỏi, “Tại sao là con, là cháu của tôi?” thường được đặt ra. Thay vì trả lời, tôi thường kể cho họ nghe câu chuyện mà tôi học được ở Thái nhiều năm về trước.

A simple forest monk was meditating alone in the jungle in a hut made of thatch. Late one evening, there was a very violent monsoon storm. The wind roared like jet aircraft and heavy rain thrashed against his hut. As the night grew denser, the storm grew more savage. First, branches could be heard being ripped off the trees. Then whole trees were uprooted by the force of the gale and came crashing to the ground with a sound as loud as the thunder.

The monk soon realized that his grass hut was no protection. If a tree fell on top of his hut, or even a big branch, it would break clean through the grass roof and crush him to death. He didn’t sleep the whole night. Often during that night, he would hear huge forest giants smash their way to the ground and his heart would pound for a while.

In the hours before dawn, as so often happens, the storm disappeared. At first light, the monk ventured outside his grass hut to inspect the damage. Many big branches, as well as two sizeable trees, had just missed his hut. He felt lucky to have survived. What suddenly took his attention, though, was not the many uprooted trees and fallen branches scattered on the ground, but the many leaves that now lay spread thickly on the forest floor.

Có một sư ẩn tu trong thảo am nằm sâu trong rừng già. Một đêm nọ mưa giông kéo đến. Gió mùa rú ghê rợn, sấm sét nổ vang trời và mưa như thác đổ. Càng về khuya mưa càng dữ dội. Tiếng cành rơi cây ngã nghe phát rợn người. Nhà sư ngồi trong am mà tâm không an vì am tranh có gì là an toàn, có thể tróc nóc hay bị cây cành đè bẹp bất cứ lúc nào. Mưa giông chỉ nhẹ hột vào lúc canh tư và dứt hẳn lúc sắp rạng đông. Đợi cho thái dương ló dạng, sư mới giở liếp bước ra quan sát sự tình.

Hai cây lớn trốc gốc. Một cây ngã cách am không đầy ba thước, thảo nào sư nghe một tiếng ầm long trời lở đất vào khoảng giữa khuya. Rủi mà may! Nhờ tàn cây này cản gió nên am sư còn đứng đó, dầu hơi xiêu vẹo và mái tranh có phần tả tơi. Cây kia nhỏ hơn và ngã xa hơn, trên mười thước. Cành khô và tươi rơi lỏng chỏng khắp mọi nơi. Lá rụng đầy rừng.

As he expected, most of the leaves lying dead on the ground were old brown leaves, which had lived a full life. Among the brown leaves were many yellow leaves. There were even several green leaves. And some of those green leaves were of such a fresh and rich green color that he knew they could have only unfurled from the bud a few hours before. In that moment, the monk’s heart understood the nature of death.

Sư bước nhẹ và chậm trên lớp lá ướt sũng nước mưa. Sư thấy đủ thứ lá rừng và đủ màu đủ sắc thiên nhiên: lớn, nhỏ, khô, ướt, nâu vàng đậm, vàng lợt, xanh đậm, xanh lợt và cả lá non mới nở nữa. Sư chợt hiểu bản chất của cái chết.

He wanted to test the truth of his insight so he gazed up to the branches of the trees. Sure enough, most of the leaves still left on the trees were young healthy green ones, in the prime of their life. Yet, although many newborn green leaves lay dead on the ground, old bent and curled up brown leaves still clung on to the branches. The monk smiled; from that day on, the death of a child would never disconcert him. When the storms of death blow through our families, they usually take the old ones, the ‘mottled brown leaves’. They also take many middle-aged ones, like the yellow leaves of a tree. Young people die too, in the prime of their life, similar to the green leaves. And sometimes death rips from dear life a small number of young children, just as nature’s storms rip off a small number of young shoots. This is the essential nature of death in our communities, as it is the essential nature of storms in a forest.

Để hiểu rõ hơn, sư nhìn lên cây và thấy là còn nhiều trên cành, nhưng hầu hết là lá xanh tươi và lá non. Dầu lá già vàng, khô rơi rụng nhiều nhưng không phải hết; trên cây vẫn còn chúng bám vào cành. Trên cành có nhiều lá non nhưng dưới đất cũng có với số lượng ít hơn. Bấy giờ sư biết tâm phân biệt của mình đã khiến mình nghĩ sai. Cơn mưa giông hồi hôm có lựa chọn cây nào, cành nào, hay lá nào để thải đâu. Cũng vậy, cái chết có thể xảy ra cho bất cứ ai, bất luận già trẻ, lớn, bé. Sư có thể mỉm cười và từ hôm ấy cái chết là cái chết và cái chết của em bé không hẳn là đáng buồn hay đáng trách hơn cái chết của ông lão.

Tâm phân biệt của sư không hoàn toàn sai nếu so sánh trước sau hay nhiều ít. Lúc cơn bão (tử thần) tới, lá “Nâu lốm đốm” (người già bệnh hoạn) thường rơi rụng trước và nhiều nhất, rồi tới lá vàng (cao niên), lá xanh đậm (trung niên), lá non (thiếu niên) và lá mới đâm chồi (sơ sanh); lá mới đâm chồi thường ít nhất.

Biết vậy, chúng ta có thể tạm kết luận rằng bản chất của tử thần trong cộng đồng không khác mấy bản chất của cơn bão trong rừng già.

There is no one to blame and no one to lay guilt on for the death of a child. This is the nature of things. Who can blame the storm? And it helps us to answer the question of why some children die. The answer is the very same reason why a small number of young green leaves must fall in a storm.

Không cần phải trách cứ ai hoặc đặt trách nhiệm lên vai ai khi cái chết xảy đến, dầu là đến với trẻ con. Đó là bản chất của sự vật. Thử hỏi ai có thể trách móc cơn bão? Và câu chuyện giúp chúng ta trả lời câu hỏi tại sao trẻ con chết. Chúng cũng giống như lá non hay lá mới đâm chồi bị rơi rụng trong cơn bão tố.

105. The ups and downs of death - Chết rồi, Đi lên hay đi xuống?

Perhaps the most emotional moment of the funeral service is the time when the coffin is lowered into the grave or, in a cremation, when the button is pressed to move the casket. It is as if the last physical reminder of a loved one is finally being stolen from the bereaved forever. It is often the moment when tears can no longer be held back.

Lúc dễ gây xúc động nhất trong đám tang có lẽ là giây phút “hạ huyệt” để chôn hay hỏa táng. Bấy giờ ai cũng có cảm tưởng mình sẽ mất người thân thương vĩnh viễn và nước mắt ít khi cầm lại được.

Such moments are particularly difficult in some crematoriums in Perth. There, when the button is pressed, the casket descends into a basement complex where the ovens are located. It is meant to replicate a burial. However, a dead person going down has the subconscious symbolism of going down to hell! It is already bad enough losing their loved one; adding the intimation of descent to the underworld is often too hard to bear.

Tôi có dịp chứng kiến nhiều lần “hạ huyệt” tại các lò hỏa táng ở Perth và được nghe nhiều người thân của kẻ quá cố thuật lại tâm trạng mình lúc họ bấm nút để quan tài tự động chìm dần xuống tầng dưới, nơi có lò thiêu. Họ nói người thân họ “đi xuống địa ngục!

Mất người thân là một cái khổ rồi, thấy người thân xuống địa ngục họ càng khổ hơn vì mặc cảm tội lỗi.

Therefore, I once proposed that crematorium chapels be constructed so that when the priest pressed the button to commit the deceased, the coffin would rise up gracefully into the air. A simple hydraulic lift would easily suffice. As the casket approached the ceiling it could disappear in swirling clouds of dry ice, and through a trapdoor into the roof cavity above, all to the sound of sweet heavenly music. What a wonderful psychological uplift that would give to the mourners!

However, some who have learnt of my proposal have advised that it might take away from the integrity of the ceremony, especially in such cases where everyone knows that the dead scoundrel in the coffin would hardly go ‘up there’. So, I refined my proposal, suggesting that there could be three buttons for committal to cover all cases: an ‘up’ button only for the goodly, a ‘down’ button to take care of the rascals, and a ‘sideways’ button for the ambiguous majority. Then, in recognition of the democratic principles of Western society, and to further add interest to an otherwise dreary rite, I could ask for a show of hands from the mourners to vote on which of the three buttons to press! This would make funeral services most memorable occasions, with a very good reason for going.

Tếu, tôi đề nghị rằng các lò hỏa táng nên thiết kế làm sao đó để khi bấm nút, quan tài từ từ đi lên thay vì đi xuống. Vấn đề không phải khó đối với kỹ thuật tối tân bây giờ. Rồi tôi vẽ cho hệ thống thang máy thủy động và dàn cảnh luôn. Tôi giải thích, lúc quan tài lên gần tới nóc, hơi nước đá khô (carbon dioxide đậm đặc) được xả ra làm thành đám mây bao quanh và nhạc êm dịu của thiên cảnh được bấm nút trổi lên đưa người quá cố qua cánh cửa nhỏ lên tầng lầu trên, nơi có lò hỏa táng. Cảm tưởng đưa người thân lên thiên đường biết đâu sẽ làm vơi nỗi u sầu của người đưa đám. Tôi kể tới đây, cử tọa cười ồ.

Nhưng có người phát biểu rằng tưởng tượng của tôi hay thì có hay, nhưng không ổn vì nếu người nằm trong quan tài là kẻ côn đồ thì sao? Tôi tiếp tục tưởng tượng thêm. Tôi đề nghị thiết kế ba nút bấm: nút “lên” cho quý vị thánh thiện, nút “xuống” cho kẻ bất thiện và nút giữa cho kẻ có tâm địa không rõ ràng. Tới giờ bấm nút, sẽ có cuộc bỏ phiếu bằng cách giơ tay, và thiểu số phải phục tùng đa số, nếu không sẽ có thêm đám tang mới (vì ẩu đả chết người)! Biết đâu hình thức bầu bán này sẽ thu hút số người đưa và đám tang sẽ hoành tráng hơn?

Chết rồi mà cũng chưa biết đi đâu. Lên hay xuống?

106. The man with four wives - Người có bốn vợ

The first wife was called Karma. The second wife’s name was Family. The third wife was Wealth. And the fourth wife was Fame.

A man, who was successful in life, maintained four wives. When his life was about to end, he called to his bedside his fourth wife, the most recent and youngest.

Ông nọ rất thành công trên đường đời nên cưới tới bốn vợ. Lúc sắp lìa trần, ông mời đến giường bệnh cô vợ thứ tư, trẻ nhất và đẹp nhất. Ông vuốt ve cô và âu yếm hỏi:

‘Darling,’ he said, stroking her legendary figure, ‘in a day or two I will be dead. After death, I will be lonely without you. Will you come with me?’

“Em à! Anh sẽ chết trong nay mai. Dưới suối vàng anh sẽ cô đơn biết bao nếu không có em. Em đi theo anh nha?”

‘No way!’ declared the illustrious girl. ‘I must stay behind. I will speak your praises at your funeral, but I can do no more.’ And she strode out of his bedroom.

“Sao được!” cô đáp gọn lỏn, “Em phải ở lại đây để tán dương Anh trong lễ tang chớ!” Nói chưa xong cô đã bỏ đi ra.

Her cold refusal was like a dagger to his heart. He had given so much attention to his youngest wife. He was so proud of her in fact that he chose her as his escort to important functions. She gave him dignity in his old age. It was a surprise to find out that she did not love him as he had loved her.

Thái độ và lời nói lạnh lùng của cô không khác gì lưỡi dao găm đâm sâu vào tim ông. Lâu nay ông rất hãnh diện về cô và đi đám tiệc quan trọng nào ông cũng đều đưa cô cùng đi, cô làm ông hãnh diện lúc tuổi về chiều. Vậy mà cô không thương ông như ông từng thương cô. Thật ông không ngờ!

Still, he had three more wives, so he called in the third wife he had married in middle-age. He had worked so hard to win the hand of his third wife. He loved her deeply for making so many joys possible for him. She was so attractive that many men desired her; yet she had always been faithful. She gave him a sense of security.

Nhưng chưa sao, vì ông còn ba bà nữa. Ông cho mời chị thứ ba mà ông cưới thời trung niên. Ông đã dày công mới đoạt được quả tim vàng này. Ông thương chị sâu đậm vì chị đã đem lại cho ông nhiều niềm vui khó quên. Chị rất duyên dáng được nhiều người dòm ngó nhưng một lòng chung thủy với ông. Hy vọng, ông nắm chặt tay chị và thỏ thẻ:

‘Sweetheart,’ he said, grasping her tightly, ‘in a day or two I will be dead. After death, I will be lonely without you. Will you come with me?’

“Em à! Anh sẽ chết trong nay mai. Dưới suối vàng anh sẽ cô đơn biết bao nếu không có em. Em đi theo anh nha?”

‘Absolutely not!’ asserted the seductive young woman in a businesslike manner. ‘Such a thing has never been done. I will give you a lavish funeral, but after the service I will go with your sons.’

“Không đâu anh”, chị trả lời với thái độ quả quyết của một nữ thương nhân, “Em cần ở lại đây để lo cho đám tang Anh thật hoành tráng, và sau đó em còn phải đi theo các con anh.”

His third wife’s future infidelity shook him to the core. He sent her away and called for his second wife.

He had grown up with his second wife. She wasn’t so attractive but she was always there for him, to help him with any problems and give invaluable advice. She was his most trusted friend.

Sự thiếu chung thủy của chị ba làm ông dao động mạnh. Ông biểu chị đi ra cho khuất mắt để ông còn cho mời bà thứ hai. Bà thứ hai là người ông tin cẩn nhất, từng giúp ông giải quyết mọi khó khăn và cho ông nhiều ý kiến quý giá. Nhìn thẳng vào đôi mắt tự tin của bà, ông hỏi:

‘Beloved,’ he said, gazing into her confident eyes, ‘in a day or two I will be dead. After death, I will be lonely without you. Will you come with me?’

“Em à! Anh sẽ chết trong nay mai. Dưới suối vàng anh sẽ cô đơn biết bao nếu không có em. Em đi theo anh nha?”

‘I’m sorry,’ she said apologetically, ‘I cannot go with you. I will go as far as your grave side, but no further.’

“Xin lỗi anh,” bà thưa với giọng hối tiếc, “Em sẽ đi theo anh đến tận nơi an nghỉ cuối cùng của anh, chớ không thể đi xa hơn.”

The old man was devastated. He called for his first wife, whom he had known seemingly forever. He had neglected her in recent years, especially after he had met his alluring third wife and distinguished fourth wife. But it was this first wife who was really important to him, working quietly behind the scenes. He felt ashamed when he saw her come in ill-dressed and very thin.

Ông như trên trời rớt xuống, hy vọng ông tan tành theo mây khói rồi. Ông bèn cho mời bà thứ nhất, người mà ông có vẻ hất hủi trong những tháng năm sau này lúc ông gặp chị ba quyến rũ và cô tư sắc nước hương trời. Nhưng bà nhất đây mới thật là người vợ mẫu mực luôn luôn đứng sau lưng ông. Ông hơi sượng sùng khi thấy bà bước vô với vẻ mặt hơi gầy và quần áo xốc xếch. Ông nói như khẩn cầu:

‘Dearest,’ he said imploringly, ‘in a day or two I will be dead. After death, I will be lonely without you. Will you come with me?’

“Em à! Anh sẽ chết trong nay mai. Dưới suối vàng anh sẽ cô đơn biết bao nếu không có em. Em đi theo anh nha?”

‘Of course, I’ll go with you,’ she replied impassively. ‘I always go with you from life to life.’

“Dĩ nhiên, em sẽ theo Anh,” bà đáp với giọng thụ động, “Em sẽ theo Anh đời đời kiếp kiếp.”

The first wife was called Karma. The second wife’s name was Family. The third wife was Wealth. And the fourth wife was Fame.

Bà thứ nhất theo ông không rời vì bà ta là nghiệp. Bà hai là gia đình, chị ba có tên Tiền tài và cô tư được gọi là danh.

Please read the story once more, now that you know the four wives. Which of the wives is most important to take care of? Which will go with you when you die?

Bây giờ các bạn đã biết rõ bốn bà vợ là ai rồi, xin các bạn đọc lại câu chuyện một lần nữa. Và theo ý các bạn, ai trong bốn bà vợ cần được chăm sóc cẩn thận nhất? Còn ai khác hơn là bà nghiệp, phải không các bạn?

107. Cracking up - Đau mà cười

In my first year in Thailand, we would be taken from monastery to monastery in the back of a small truck. The senior monks had the best seats, of course, in the cab up front. We junior monks sat squashed on hard wooden benches on the rear tray. Above the benches was a low metal frame, over which was stretched a tarpaulin to protect us from rain and dust.

Năm đầu tiên tôi tu ở Thái Lan, tôi được di chuyển từ chùa này qua chùa khác bằng xe vận tải nhỏ. Sư lớn được ngồi phía trước gần tài xế còn sư trẻ chúng tôi phải chen chúc trên hai cái ghế cây dài trong thùng xe đằng sau. Thùng xe có mui vải bố trùm trên các thanh sắt chữ U lật ngược.

The roads were all dirt roads, poorly maintained. When the wheels met a pothole, the truck went down and the junior monks went up. Crack! Many times, I cracked my head on those hard metal frames. Moreover, being a bald-headed monk, I had no ‘padding’ to cushion the blow.

I swore every time I hit my head—in English, of course, so the Thai monks couldn’t understand.

Lúc bấy giờ, lộ ở đây là những con đường đất không được tu bổ nên lồi lõm bất thường. Mỗi khi xe lọt xuống ổ voi chúng tôi nhảy vọt lên và đụng đầu vô sườn sắt nghe lốp cốp. Cái đầu trọc của tôi thật đáng tội và tôi không thể nào không chửi thề - dĩ nhiên chửi bằng tiếng Anh để các sư bạn không biết.

But when the Thai monks hit their heads, they only laughed! I couldn’t figure it out. How can you laugh when you hit your head so painfully hard? Perhaps, I considered, those Thai monks had already hit their heads too many times and there had been some permanent damage.

Nhưng các sư Thái lại cười. Tôi không hiểu sao họ cười được khi bị đụng đầu đau điếng như vậy. Phải chăng đầu họ chai nên không đau? Hay họ cố cười để quên cái đau?

Because I used to be a scientist, I decided to do an experiment. I resolved to laugh, like the Thai monks, the next time I cracked my head, just to see what it was like. You know what I discovered? I found out that if you laugh when you hit your head, it hurts much less.

Vì óc tò mò của một thầy giáo dạy khoa học trước đây, tôi thử nghiệm một phen xem sao. Mỗi lần bị đụng đầu tôi cười. Cười, tôi cảm thấy ít đau hơn chửi. Cũng hay hay!

Laughter releases endorphins into your bloodstream, which are nature’s painkillers. It also enhances your immune system to fight off any infections. So, it helps to laugh when you feel pain. If you still don’t believe me, then try it the next time you hit your head.

Cười giúp thảy ra máu chất endorphin có công dụng làm giảm đau và tăng sức đề kháng của cơ thể. Do đó cười làm dịu cơn đau. Nếu không tin xin các bạn thử sẽ biết liền.

The experience taught me that when life is painful, it hurts less when you see the funny side and manage a laugh.

Kinh nghiệm dạy rằng đời có mặt trái của nó với nhiều chuyện nực cười. Vậy chúng ta nên nhìn vào mặt trái này và cười lớn mỗi khi bị đời vùi dập. Cười nhiều, đau khổ sẽ ít đi.

108. The worm and his lovely pile of dung - Con trùn và đống phân

Some people simply don’t want to be free from trouble. If they haven’t got enough problems of their own to worry about, then they tune in to the television soapies to worry about fictional characters’ problems. Many take anxiety to be stimulating; they regard what is suffering to be good fun. They don’t want to be happy, because they are too attached to their burdens.

Nhiều người không chịu ở không. Khi có chút thoải mái rồi, họ tìm cách ôm lấy phiền toái của người khác. Ví dụ: họ thích mở truyền hình theo dõi tình tiết của các bộ phim dài lê thê để thương vay khóc mướn hoặc hồi hộp với các pha cao bồi bắn súng. Họ thích được lo âu và buồn khổ. Họ chẳng những không chọn hạnh phúc mà còn buộc cho mình vào khổ đau, thứ khổ đau mà đáng lẽ họ không cần phải gánh chịu.

Two monks had been close friends all their life. After they died, one was reborn a deva (a heavenly being) in a beautiful heaven world, while his friend was reborn as a worm in a pile of dung.

The deva soon began to miss his old friend and wondered where he’d been reborn. He couldn’t find his friend anywhere in his own heaven world, so he looked in all the other heaven realms too. His friend wasn’t there. Using his heavenly powers, the deva searched the world of human beings but couldn’t find his friend there either. Surely, he thought, his friend wouldn’t have taken rebirth in the animal realm, but he checked there just in case. Still there was no sign of his friend from the previous life. So, next, the deva searched the world of what we call the ‘creepy-crawlies’ and, to his great surprise, there he found his friend reborn as a worm in a disgusting pile of stinking dung!

Có hai nhà sư cùng tu trong một tự viện và thương nhau như anh em ruột thịt. Sau khi lìa đời, hai sư tái sanh theo hai nẻo duyên nghiệp riêng của mỗi người. Sư em tái sanh làm thiên tử sống tự tại trên cõi trời. Một hôm nhớ anh, sư em đi tìm. Sư tìm khắp mấy từng trời nhưng không thấy anh. Xuống cõi người sư cũng không thấy. Lục lạo thêm dưới các cõi ác để cầu may vì sư không tin anh mình đến đỗi bị đọa xuống đây. Nhưng sư em ngạc nhiên khi nhận ra anh đang làm con trùn sống trong đống phân.

The bonds of friendship are so strong that they often outlast death. The deva felt he had to rescue his old companion from such an unfortunate rebirth, no matter what karma had led to it. So, the deva appeared in front of the foul pile of dung and called out,

Thương anh, vị thiên tử muốn cứu trùn ra khỏi cảnh khổ bất kể nghiệp của trùn. Ông đến đống phân gọi:

‘Hey, worm! Do you remember me? We were monks together in our past life and you were my best friend. Whereas I’ve been reborn in a most delightful heaven world, you’ve been reborn in this revolting pile of cow-shit. Don’t be worried, though, because I can take you to heaven with me. Come on, old friend!’

“Này trùn, huynh có nhận ra đệ không? Chúng ta từng là huynh đệ trong kiếp trước nè. Đệ đang làm thiên tử sống trên cõi trời và muốn đưa Huynh lên cùng sống trên đó. Huynh đi nha?”

‘Hang on a moment!’ said the worm, ‘What’s so great about this “heaven world” you are twittering on about? I’m very happy here with my fragrant, delicious pile of delectable dung, thank you very much.’

“Cám ơn đệ,” trùn nói. “Có gì vui sướng trên cõi thiên mà đệ oang oang vậy? Huynh đang rất hạnh phúc trong đống phân tuyệt diệu này.”

‘You don’t understand,’ said the deva, and he gave the worm a brilliant description of the delights and pleasures of heaven.

‘Is there any dung up there, then?’ asked the worm, getting to the point.

‘Of course not!’ sniffed the deva.

‘Then I ain’t going!’ replied the worm firmly. ‘Nick off!’ And the worm burrowed into the center of the dung pile.

“Huynh không biết đó chớ,” vị thiên tử đáp rồi bắt đầu mô tả những kỳ diệu của thiên cảnh.

“Trên đó có phân không, thưa đệ?” Trùn đặt thẳng vấn đề.

“Dĩ nhiên là không.” Vị thiên tử thật thà đáp.

“Vậy huynh xin được từ chối.” Vừa nói trùn vừa chui vô đống phân.

The deva thought that if only the worm could see heaven for himself, then he would understand. So, the deva held his nose and thrust his soft hand into the repulsive pile of dung, searching for the worm. He found him and began to pull him out.

Nghĩ rằng trùn sẽ thích thú với thiên giới nếu được thấy tận mắt, vị thiên tử không nề hà đưa tay bới phân tìm trùn. Ông kéo trùn ra, nhưng trùn giãy giụa và la lớn:

‘Hey! Leave me alone!’ screamed the worm. ‘Help! May Day! I’m being worm-napped!’ And the little slippery worm wriggled and squirmed till he got free, then he dived back into the dung pile to hide.

The kind deva plunged his fingers into the stinking faeces again, found the worm and tried once more to pull him out. The deva almost got the worm out, but because the worm was smeared with slimy filth and did not want to go, he escaped a second time and hid even deeper in the dung pile. One hundred and eight times the deva tried to lead the poor worm out from his miserable dung pile, but the worm was so attached to his lovely pile of dung that he always wriggled back!

So, eventually, the deva had to go back up to heaven and leave the foolish worm to his ‘lovely pile of dung’.

“Xin buông huynh ra. Đừng bắt cóc trùn!” Rồi trùn trơn vuột khỏi tay vị thiên tử và chui trở vô đống phân. Vị thiên tử moi tìm lại và bắt được trùn lần thứ hai. Như lần trước trùn tiết chất nhờn trở thành trơn chùi, lọt khỏi kẽ tay và trốn dưới đống phân. Trì chí, vị thiên tử lập lại lần thứ ba, thứ tư… thứ một trăm lẻ tám. Nhưng trùn đã gắn bó quá sâu đậm với đống phân rồi nên không muốn bỏ đi. Sau cùng vị thiên tử đành trở về thiên cung, tay không.

Thus, end the hundred and eight stories told in this book.

Chuyện thứ một trăm lẻ tám vừa kể kết thúc quyển sách nhỏ này.

Because the coconut is delicious. I ain’t letting it go!!!

Sources:

Tài liệu tham khảo:

- https://tienvnguyen.net/p147a888/chuong-11-

- https://www.bps.lk/olib/bp/bp619s_Brahm_Opening-The-Doors-Of-Your-Heart.pdf

- Photo 2: http://burmadhamma.blogspot.com/2019/10/

- Photo 3: https://contexts.org/articles/digging-for-mutual-cooperation/

- Photo 4: https://path2inspiration.com/blogs/news/poor-me-lucky-them

- Photo 5: https://microbiologyinfo.com/scrub-typhus-etiology-epidemiology-symptoms-pathogenesis-diagnosis-and-treatment/

- Photo 6: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Samuel_Butler_(novelist)

- Photo 7: https://www.pilotonline.com/news/health/vp-nw-coronavirus-nursing-homes-closed-to-visitors-20200318-jfz3a7dqubfy7bwkrugj5vagpi-story.html

- Photo 8: https://blog.sevenponds.com/cultural-perspectives/funeral-rites-in-the-buddhist-tradition

- Photo 9: https://rusticescentuals.com/Falling-Leaves.html

- Photo 10: https://dontgiveupworld.com/the-story-of-a-man-with-four-wives/

- Photo 11: http://evdhamma.org/index.php/dharma/dharma-lessons/item/1134-khong-ton-tai-song-ngu

![[7-12] - Chuyện Vui Ngắn - Short Funny Stories – Song ngữ [7-12] - Chuyện Vui Ngắn - Short Funny Stories – Song ngữ](/images/resized/59b514174bffe4ae402b3d63aad79fe0_7-12._title_224_120.png)

![[13-20] - Chuyện Vui Ngắn - Short Funny Stories – Song ngữ [13-20] - Chuyện Vui Ngắn - Short Funny Stories – Song ngữ](/images/resized/fa447a14965dfd70772de1948c4d467d_13-20._title_224_120.png)